In statistics, we draw a sample from a population and use the things we observe about the sample to make generalizations about the entire population. For example, we might present a subset of visitors to a website with different versions of a page to get an estimate of how ALL visitors to the site would react to them. Because there is always random variability (error), we don't expect the sample to be a perfect representation of the population. However, if it's a reasonably large, well-selected sample, we can expect that the statistics we calculate from it are fair estimates of the population parameters.

Bias is anything that leads to a systematic difference between the true parameters of a population and the statistics used to estimate those parameters. Here are a few of the most common types of bias and what can be done to minimize their effects.

Bias in Sampling

In an unbiased random sample, every case in the population should have an equal likelihood of being part of the sample. However, most data selection methods are not truly random.

Take exit polling. In exit polling, volunteers stop people as they are leaving the voting place and ask them who they voted for. This method leads to the exclusion of those who vote by absentee ballot. Furthermore, research suggests the people are more likely to gather data from people similar to themselves.

Polling volunteers are more likely to be young, college educated, and white compared with the general population. It's understandable that a white college student will be more likely to approach someone who looks like they could be one of their classmates than a middle-aged woman, struggling to keep three children under control by speaking to them in a language the student does not understand. This means not every person has the same chance of being selected for an exit poll.

Bias in Assignment

In a well-designed experiment, where two or more groups are treated differently and then compared, it is important that there are not pre-existing differences between the groups. Every case in the sample should have an equal likelihood of being assigned to each experimental condition.

Let's say the makers of an online business course think that the more times they can get a visitor to come to their website, the more likely they are to enroll. And in fact, people who visit the site five times are more likely to enroll than people who visit three times, who are – in turn – more likely to enroll than people who visit only once.

The marketers at the online school might mistakenly conclude that more visits lead to more enrollment. However there is are systematic differences between the groups that precede the visits to the site. The same factors that motivate a potential student to visit the site five times rather than once may also make them more likely to enroll in the course.

Omitted Variables

Often links between related variables are overlooked, or links between unrelated variables are seen, because of other variables that have an impact but haven't been included in the model.

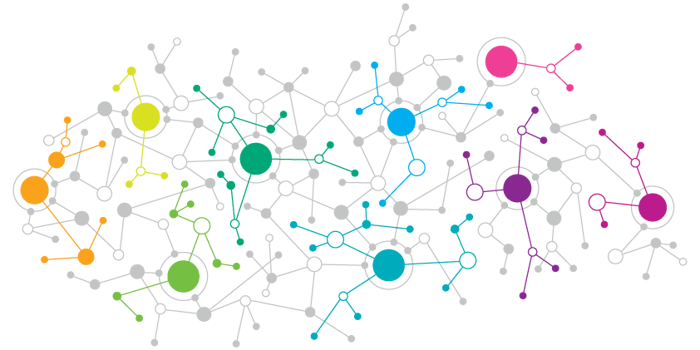

For example, in 1980, Robert Matthews discovered an extremely high correlation between the number of storks in various European countries and the human birthrates in those countries. Using Holland as an example, where only four pairs of storks were living in 1980, the birth rate was less than 200,000 per year, while Turkey, with a shocking 25,000 pairs of storks had a birth rate of 1.5 million per year.

In fact, the correlation between the two variables was an extremely significant 0.62! This isn't because storks bring babies, but rather that large countries have more people living in them, and hence higher birth rates—and also more storks living in them.

Rerunning the analysis including area as an independent variable solves this mystery. Many other (more amusing) spurious correlations can be found at tylervigen.com. While it may not be possible to identify all omitted variables, a good research model will explore all variables that might impact the dependent variable.

Self-serving Bias

There are a number of ways that surveys can lead to biased data. One particularly insidious challenge with survey design is self-report bias. People tend to report salary and education as higher than reality, and weight and age as lower.

For example, a study might find a strong correlation between a good driver and being good at math. However, if the data were collected via a self-report tool, such as a survey, this could be a side effect of self-serving bias. People who are trying to present themselves in the best possible light might overstate both their driving ability and their math aptitude.

Experimenter Expectations

If researchers have pre-existing ideas about the results of a study, they can actually have an impact on the data, even if they're trying to remain objective. For example, interviewers or focus group facilitators can subtly influence participants through unconscious verbal or non-verbal indicators.

Experimenter effects have even been observed with non-human participants. In 1907, a horse named Clever Hans was famous for successfully completing complex mathematical operations and tapping out the answer with his hoof. It was later discovered that he was responding to involuntary body language of the person posing the problems. To avoid experimenter expectancy, studies that require human intervention to gather data often use blind data collectors, who don't know what is being tested.

In reality, virtually all analyses have some degree of bias. However, attention to data collection and analysis can minimize it. And this leads to better models.

Interested in expanding your business vocabulary and learning the skills Harvard Business School's top faculty deemed most important for any professional, regardless of industry or job title?

About the Author

Jenny is a member of the HBX Course Delivery Team and currently works on the Business Analytics course for the Credential of Readiness (CORe) program, and supports the development of a new course in Management for the HBX platform.

Jenny holds a BFA in theater from New York University and a PhD in Social Psychology from University of Massachusetts at Amherst. She is active in the greater Boston arts and theater community, and she enjoys solving and creating diabolically difficult word puzzles.

.png?width=658&name=A-B%20Test(1).png)

From a very young age, I was interested in design. Toys that could be infinitely reconfigured like Legos and SimCity captured my imagination for hours. Interests at home influenced my interests at school, and by age 13, they had coalesced into the goal of becoming an engineer. This drive grew, and propelled me for over a decade, to graduation day at Boise State University. I had done it. I had become a Civil Engineer and had landed a job in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math).

From a very young age, I was interested in design. Toys that could be infinitely reconfigured like Legos and SimCity captured my imagination for hours. Interests at home influenced my interests at school, and by age 13, they had coalesced into the goal of becoming an engineer. This drive grew, and propelled me for over a decade, to graduation day at Boise State University. I had done it. I had become a Civil Engineer and had landed a job in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math). received his undergraduate degree in Civil Engineering from Boise State University and has spent over 10 years working on infrastructure in transportation and waste water collection systems. Kyle is an advocate for mentorship and community involvement, leading the professional development programs for the Boise Young Professionals Network and volunteering on a regular basis.

received his undergraduate degree in Civil Engineering from Boise State University and has spent over 10 years working on infrastructure in transportation and waste water collection systems. Kyle is an advocate for mentorship and community involvement, leading the professional development programs for the Boise Young Professionals Network and volunteering on a regular basis.

Jackie is a member of the HBX Course Delivery Team and currently works on the Financial Accounting course for the Credential of Readiness (CORe) program. She also works on the Leading with Finance Course, and is working to design and develop a course in Entrepreneurship for the HBX Platform.

Jackie is a member of the HBX Course Delivery Team and currently works on the Financial Accounting course for the Credential of Readiness (CORe) program. She also works on the Leading with Finance Course, and is working to design and develop a course in Entrepreneurship for the HBX Platform.