If you've been following the election at all, you've probably noticed that some polls give very different estimates of who's likely to win the presidency in November. For example, at 1:00 PM EDT on Tuesday, September 27th [this will probably change by the time you read this]:

- The New York Times shows Clinton leading 45% to 42%

- The Los Angeles Times reports Trump leading 46.2% to 42.7%

- HuffPost Pollster shows Clinton up 47.6% to 44.1%

- Data analysis site FiveThirtyEight gives three different estimates:

- Their Polls-only forecast is 55.8% to 44.2% in Clinton's favor

- Their Polls-plus forecast (which includes such factors as the economy and event-related spikes in either candidate's favor) is 55.2% to 44.7% in Clinton's favor

- Their nowcast (what they'd expect if the election were held today) is 52.7% to 47.3% in Clinton's favor

There are a number of reasons for this: they poll different people, using different questions, via different media. For example, polls that use only mobile numbers, and exclude landlines, tend to under-sample older voters. And wording changes as simple as which candidate is mentioned first by the poll can affect responses.

But the biggest differences may be caused by weighting, a method used to make the sample (which may be demographically different from the expected voter turnout) look like the population. Each organization uses its own weighting algorithm, leading to a diversity of predictions. In fact, the New York Times recently shared poll data it had collected with four well-respected analysts.

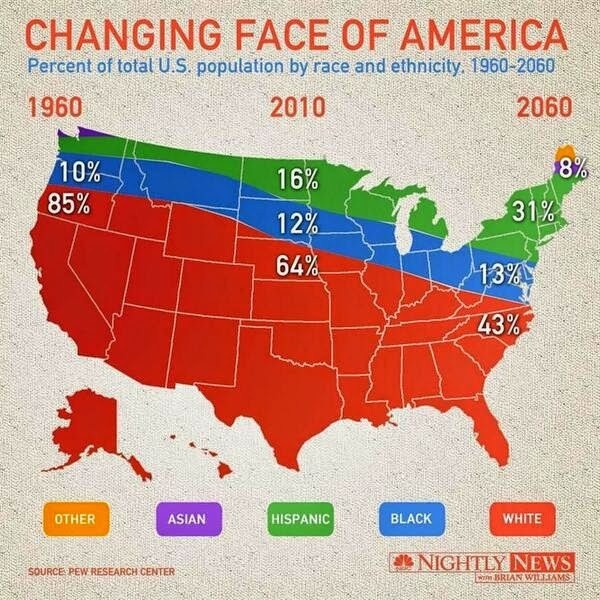

Even with the exact same data, the different weighting methods led to results varying from a four point lead for Clinton to a one point lead for Trump. That's because each organization has a slightly different idea of what the electorate will look like in terms of gender, ethnicity, education, socio-economic status, etc. These assumptions about who will vote influence what the polls tell us.

One thing is pretty clear: this will be a tight race, and people seem more emotionally invested in it than they have been in many recent elections. And given last night's debate, the numbers will likely fluctuate in the upcoming days.

Interested in learning more about how to interpret data? Take HBX CORe and discover the basics of Economics for Managers, Financial Accounting, and Business Analytics.

About the Author

Jenny is a member of the HBX Course Delivery Team and currently works on the Business Analytics course for the Credential of Readiness (CORe) program, and supports the development of a new course in Management for the HBX platform. Jenny holds a BFA in theater from New York University and a PhD in Social Psychology from University of Massachusetts at Amherst. She is active in the greater Boston arts and theater community, and she enjoys solving and creating diabolically difficult word puzzles.