On June 16, Amazon announced that they would be purchasing Whole Foods for $13.7 billion - approximately 27% higher than its current value in the market. After the initial shock wore off, many people began to speculate about whether this was a good decision or not.

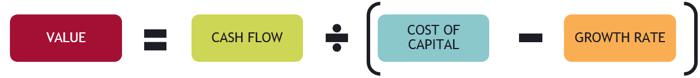

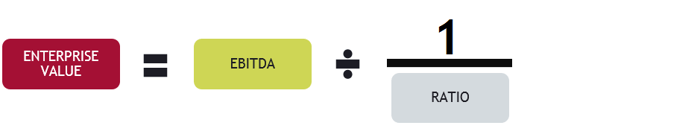

In finance, we think about creating value as generating returns in excess of a firm's cost of capital - in other words, for projects and decisions to generate more cash flow over time than they cost today to implement, discounted back to the present.

That's a mouthful of a definition, but even the best projections can't necessarily help us understand if our decisions were successful. This is one place where the stock market – the crowdsourced opinions of thousands of analysts – can be of assistance.

Imagine a market value balance sheet; on the left side, the Assets side, are the market value of the firm's cash and their operating assets. On the right side, to balance, are the market value of the firm's debt and the market value of their equity. Now imagine that the firm makes an investment - they use $1 million dollars in cash and make a $1 million investment in a new asset. Accounting will shift the balance from cash to operating assets and show no change. But did the value of the firm change?

For this, we can look at the other side of the balance sheet - the financing side. Unless new debt is taken on as part of the project, the debt portion should stay the same. Which means that any decision that creates or destroys value for the firm will show up immediately in the market value of equity, which we call "market capitalization." The market capitalization tends to reflect the consensus opinion of decisions instantly, as all of those thousands of analysts respond to firm announcements in real time.

We can think of the purchase of Whole Foods as an investment decision - Amazon took a certain amount of cash and purchased an asset. Was that a value creating or value destroying decision?

In acquisitions, value creation comes from synergies, or ways in which the two companies together are worth more than they are individually. Sometimes, the acquiring company overpays for the acquisition, giving most or all of the synergies to their target. Sometimes they overpay by so much that they destroy value. So what about Amazon? How did they do?

For this, we can look at the market value of their equity. On Thursday, June 15, Whole Foods had a market capitalization of $10.6 billion and Amazon had a market capitalization of $460.9 billion. By the end of trading on Friday, Whole Foods' market capitalization was $13.7 (which makes sense, that's the price they were being acquired at) and Amazon's was $472.1 billion.

That means that the market thinks this acquisition created $14.3 billion in value through synergies (the total combined increase across the two companies) and the synergies were split up by giving $3.1 billion to Whole Foods shareholders and $11.2 billion to Amazon shareholders.

Clearly, the market felt this was a really good decision (and the market capitalizations of the two companies continued to rise over the next week). In fact, since the synergies at $14.3 billion are more than the purchase price of Whole Foods at $13.7, it can be said that the market thinks Whole Foods is worth twice as much as part of Amazon than it is alone. That's incredible - and it's how the market consensus can tell firms, instantly, whether their decisions created value.

Want to better understand finance? Interested in developing a toolkit to make smarter financial decisions? Learn more about the HBX course, Leading with Finance.

About the Author

Brian is a member of the HBX Course Delivery Team and was the lead content specialist for the HBX Leading with Finance course. He is currently working to build courses on entrepreneurship, management, and corporate social responsibility. He is a veteran of the United States submarine force, has a background in the insurance industry, and holds an MBA from McGill University.