We sat down with Geri Fox from our admissions team to talk about the HBX application process. Curious what makes for a successful applicant? Read on!

What do you do at HBX?

My official title is Associate Director of Enrollment  Management. What that means is that I work closely with the admissions team, product management,and marketing teams to understand

Management. What that means is that I work closely with the admissions team, product management,and marketing teams to understand

the qualifications a participant needs to be successful in a particular HBX course. My team then evaluates applicants accordingly.

What does a normal day look like for you?

For me, a typical day at HBX involves reviewing applications from people who have applied to any of our five programs, tracking how the applicant and registrant pools are shaping up, and keeping a close eye on our yield (the percent of people who register of those we admit). I also spend a great deal of time with our development team planning and testing new functionality to improve our application and administrative systems.

What makes a good candidate for HBX programs?

A strong candidate for a HBX course is someone with proven academic success who shows determination to get through an intensive course. Candidates should also demonstrate an interest in being a strong community member, willing to share knowledge and help others.

What does the typical HBX student look like?

Truthfully, there is no typical HBX student. Our students come from incredibly diverse backgrounds. We have students who are in graduate school, others who are undergraduates, and some who have worked for over 25 years. We have students who come from very different industries and from nearly every country around the world. HBX students are doctors, English majors, engineers, lawyers, IT professionals, and entrepreneurs. Essentially, there is a broad range of people who find value and succeed in our courses.

Truthfully, there is no typical HBX student. Our students come from incredibly diverse backgrounds. We have students who are in graduate school, others who are undergraduates, and some who have worked for over 25 years. We have students who come from very different industries and from nearly every country around the world. HBX students are doctors, English majors, engineers, lawyers, IT professionals, and entrepreneurs. Essentially, there is a broad range of people who find value and succeed in our courses.

What does the application process for an HBX course look like?

Our applications vary slightly depending on the course you apply to. Generally speaking, it includes the following:

- Biographical information: address and phone number

- Educational history: school attending (or attended) and degrees received

- Employment information (if applicable): years of work experience, industry, and function

- Short Essay: up to 300 words in response to a basic open-ended question

How long will it take me to hear back?

You should expect to receive an admissions decision from us approximately one week after your application is submitted.

You should expect to receive an admissions decision from us approximately one week after your application is submitted.Any tips on how to write a great application?

It is important to submit a thorough application and to be as honest as possible. Our goal is to get to know a bit about you through the application and, since we aren’t able to meet in person, this is the next best thing.

Do military members get a discount? How do they note their military status in the application?

Military members and veterans do in fact get a discount. In the application we request proof of military status or proof that you are a veteran. There are clear directions within the application on how to provide documentation.

What's your favorite book?

A Prayer for Owen Meany by John Irving.

Do you have any hidden talents?

I am really good at Dance Dance Revolution!

TV show you never miss?

I never miss a Game of Thrones episode.

Favorite food?

My favorite food is a cannoli from Mike’s Pastry in Boston's North End.

Ben is a member of the HBX Course Development Team and works on the Negotiation Mastery and Economics for Managers courses. He has a background in economics and physics and enjoys card games, cooking, and discussing philosophy.

Ben is a member of the HBX Course Development Team and works on the Negotiation Mastery and Economics for Managers courses. He has a background in economics and physics and enjoys card games, cooking, and discussing philosophy.

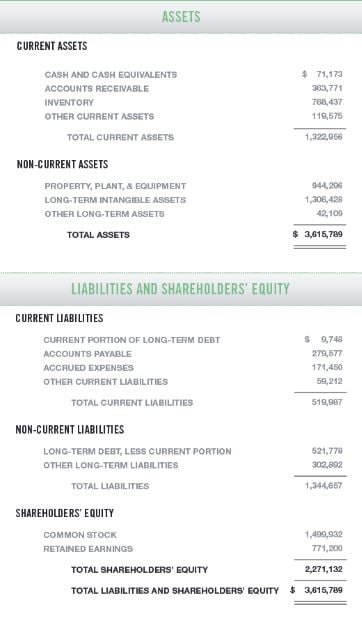

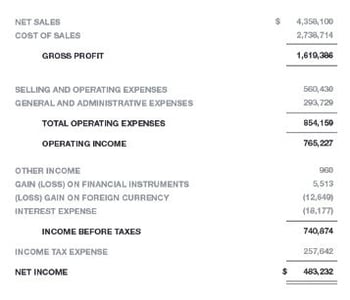

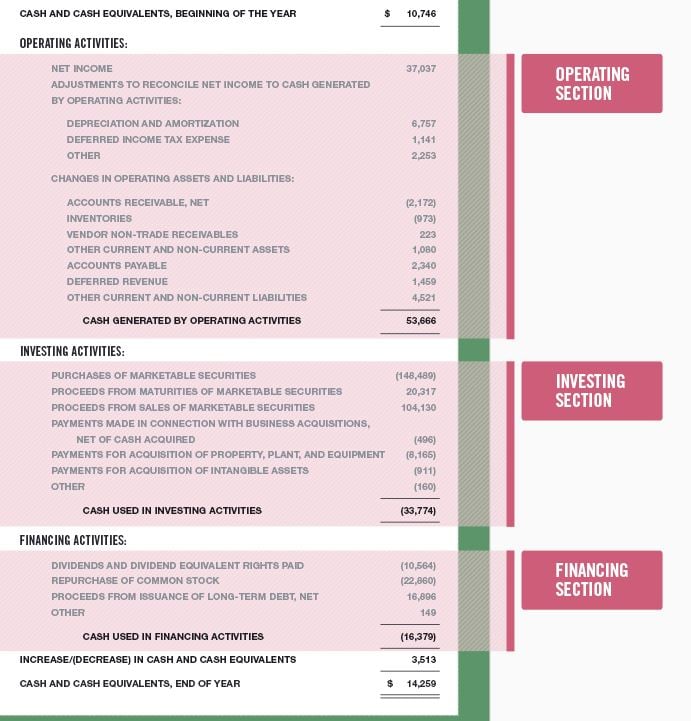

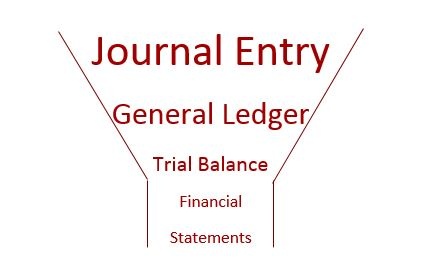

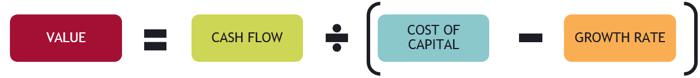

Jackie is a member of the HBX Course Delivery Team and currently works on the Financial Accounting course for the Credential of Readiness (CORe) program. She also works on the Leading with Finance Course, and is working to design and develop a course in Entrepreneurship for the HBX Platform.

Jackie is a member of the HBX Course Delivery Team and currently works on the Financial Accounting course for the Credential of Readiness (CORe) program. She also works on the Leading with Finance Course, and is working to design and develop a course in Entrepreneurship for the HBX Platform.